April 24, 2024 | Jack Jeffress x Helly Hansen

FROM THE FJORDS OF NORWAY TO THE VAST EXPANSES OF ANTARTICA

Discover the fantastic adventures of Jack Jeffress, photographer, computer programmer, and expert expedition guide, as he answers the call of the ice and braves the icy landscapes with Helly Hansen by his side.

For years, I'd been feeling "something" over and over again, but I just couldn't find a way to explain it. It was a deep yearning, almost to the point of irritability – there was no escape no matter how hard I tried. The more I ignored it, the more it prevailed. I was convinced there was no word for this feeling in any dictionary, I'd searched and scoured too thoroughly. And despite all that searching, the unknown feeling continued to taunt me. Then, one day, I stumbled across a single Danish word.

I'd been reading about explorers for as long as I could remember, finding escapism through those who pushed their limits far beyond what seemed possible. For whatever reason, those who went to the far north or south were the people who fascinated me the most. Amundsen, Shackleton, Scott, Mawson, Ross and many, many more. Their stories of the ends of the Earth, the relentless challenges they faced and the unrivalled beauty they witnessed, echoed in my mind. The photos by people like Frank Hurley were animated in my dreams.

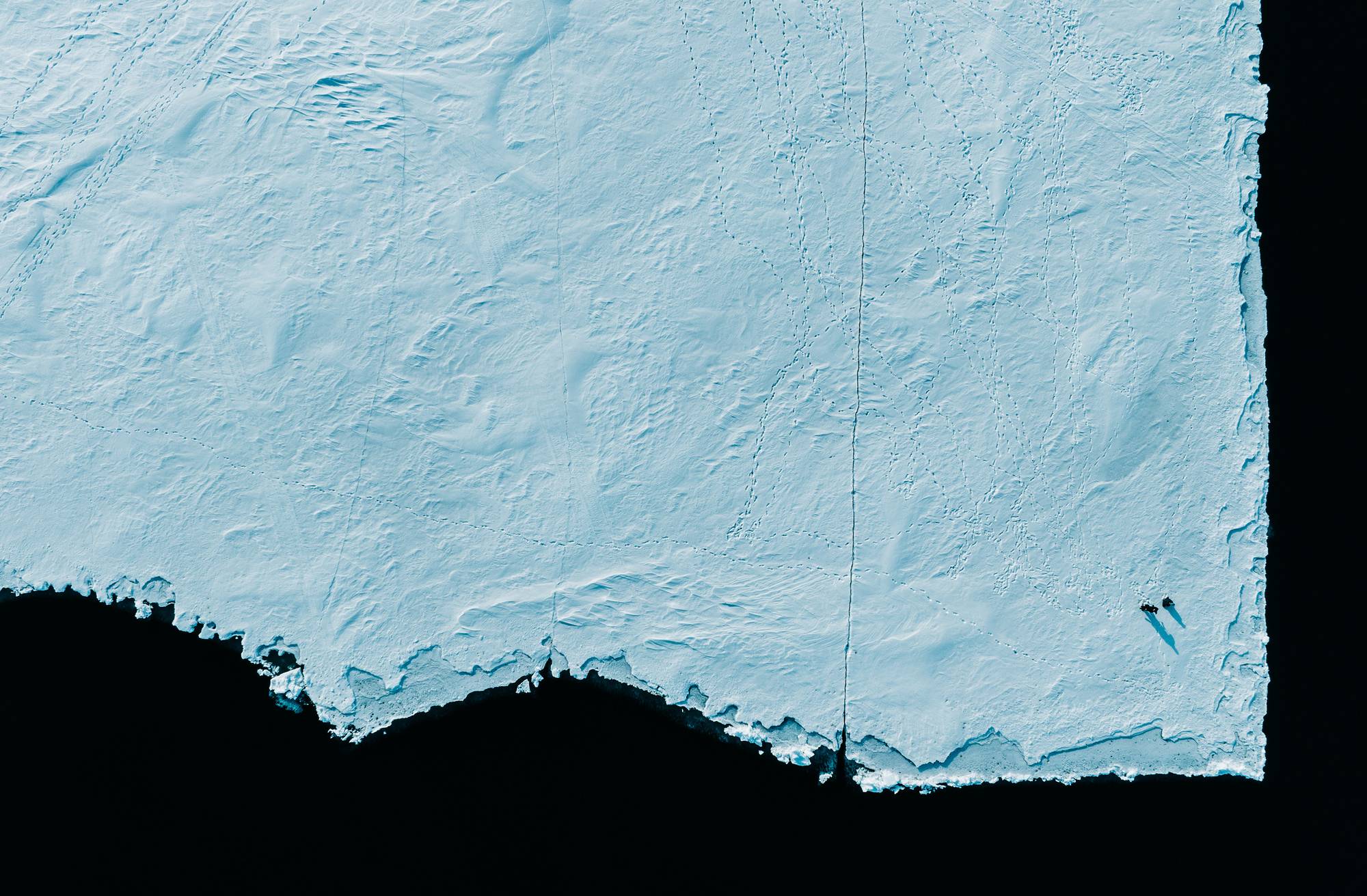

_Photo Jack Jeffress

In retrospect, it should've been obvious. The Danish word that cleared the fog of yearning was “Polarhullar”, and it means ‘an ache for the polar regions’. In a single word, it spoke of an insatiable pull, reeling in those lucky enough to have visited back to the frozen worlds. As soon as I heard it, I finally understood. That's exactly what I had been feeling. Memories of my time in the ice kingdoms began to flood my mind.

I’ve been fortunate enough to have experienced some amazing journeys in the polar regions, and each trip has been better than the last. Every time you go, you are enveloped by a frozen wilderness like no other and each expedition demands meticulous preparation and absolute respect.

There are many different ways to get "there", wherever that is. Some parts you can drive to, but more likely it will be a stormy ocean crossing, a bumpy ride in a light plane or helicopter, a challenging run in a snowmobile, or a slow step by step trek or ski into the ice. Some have even gone in hot air balloons, with varying degrees of success. However you get to the polar regions though, there will inevitably be a moment of clarity when you realise you have left civilisation and all of the creature comforts behind. Without exception, it is a strange feeling. The change is too drastic for it to go unnoticed. This moment on my last trip to the Canadian Arctic was particularly powerful.

After landing on the ice in a small plane, we spent an evening in a quiet Inuit village. The people were as welcoming and strong as any I'd met before. Surviving 15,000 years in an environment like this? Without that incredible resilience, it's not possible. Against a background of the murmurs and howls of sled dogs, and of ice underfoot, the Inuktitut language and its beautiful rhythm echoed everywhere we walked.

We were welcomed in an almost unimaginable way. We played games, took part in tradition, listened to music, and ate well. Stories of the Nanuq (Polar Bear) and great Walrus Skulls in the sky were told, as hunters returned from the tundra with seal and narwhal. This community survives as one, it's the only way it could ever work in such a hostile landscape. And so, the food the hunters brought back was shared with everyone immediately and without expectation of anything in return. The stories and games continued. Laughter skipped across the ice until well into a night which still looked like day. I don't know how long we were all together that evening. I do know that we were family in those moments, and still are.

But all too soon it was time to leave. We checked our gear, checked each other's gear, double-checked, triple-checked and then some. When we were finally ready to set off, half the team climbed onto the snowmobiles and the others clambered into the komatiqs – the small, coffin-like wooden boxes we towed, used for sleeping and storage. Then it began.

We started our journey through the great fjords to the windswept tundra and floe edge. Looking back as we were driving out, we saw the smiles and well-wishes of all the incredible people we had forged such strong bonds with. That was the last time we would see anyone else for a while. It was also the last of the internet, the messages from home, electricity, running water and all those other conveniences we had gotten used to. It was just us, and the great white north. Adrenaline coursed through our veins, anticipation, fear, excitement, and purpose filled our minds. There was no place we’d rather be.

Polar regions are presented in so many different ways, but few do them any sort of justice at all. Whether empty fields of white, towering icebergs, massive mountains and sea cliffs, endless frozen dunes, or wildlife congregations of such an immensity that they don't make sense – the one constant is a scale that defies belief. In that grandeur, hidden secrets lie.

You soon learn the empty fields of white aren’t empty at all, that not all ice is created equal and that any distance covered here is distance hard-earned.

Jack wearing the Arctic Patrol Modular Parka.

Our most advanced parka to date made for the harshest cold conditions there are.

What looks like a vast, blank canvas is actually a rugged mosaic. The forces on the ice are so immense that pressure ridges and ice berms form, and tented, hummocked and rafted ice reach out to the sky. There are deep cracks and fractures in the sea ice, creating leads of open water that must be crossed. The sastrugi, great frozen dunes of the far north and south, rise and fall as far as the eyes can see. Glaciers hide their infinite depths below. And ice is not always white. Sometimes it is a rich blue or a deep green. Icebergs, landlocked or otherwise, are the frozen giants serving as guardians over this desolate place. And in the middle of all of this, are the polynyas. Areas of open water so filled with life that it can be difficult to find a place to enter.

Nature is indifferent. It isn't out to get to you, but in a place as hostile as this, it shows no mercy. It merely tolerates us for the moments it chooses to. There are hurdles to overcome in every direction. A momentary loss of attention, a lapse of judgement, an equipment failure, an unexpected twist – you are one step away from potentially dire consequences. You learn quickly that everything has to be calculated. You are a trespasser in these areas and in a lot of ways you don't belong. All you can be is prepared, patient, diligent, and have complete trust in your team and gear. Don't get me wrong, comfort levels do increase trip after trip, but that must come from experience, rather than complacency. You do learn to read the signs, however you can never drop your guard or take anything for granted.

Though these areas are very difficult to navigate, they also possess otherworldly beauty. From whichever perspective you choose to take, awe is unavoidable. When looking closely, there are patterns everywhere - endless fractals and reflections splintering outside your view. When looking from far away or up high, there's a depth to the landscape that is uncanny. Giant ice castles rise from the flats and reach to the heavens, on a canvas constantly redefined by the weather. Sometimes it can feel as if you are walking on the bones of the Earth.

It's an assault on the senses, and to be honest, that was one of the things I was most surprised by on my first trips to these frozen worlds.

There's a remarkable contrast in the beginning of a polar trip. Before the journey, you are in settings so social and full of life that it’s hard to imagine anything else. They are soon replaced by a deafening silence. It takes a while for your mind to adapt - the sounds and sights confuse you. When you first get on the snowmobiles it's hard to recognise the surface underneath, but it doesn't take long before you can read the ice – whether it’s sturdy enough, too hard, too thin or too soft. When you first go to sleep on a boat encircled by ice, it’s shocking as growlers scrape past, with screeches and shudders that feel like the hull is being torn apart. Though it’s never a good thing, and always unsettling, eventually you become used to it. Sometimes, if there is a moment between tasks, you hear the ice groan and crease and crack. Whether that is the movements of the ice, the water beneath, indications of a changing environment or the sounds of a bowhead whale pushing through the ice – when hearing it, it can be a little disconcerting. Soon enough, you come to appreciate the ice is almost a living thing – constantly moving, taunting and shifting. When that happens you settle with understanding.

The landscape’s challenges are undeniable, and the weather is your constant companion - sometimes an ally, all too often a deadly adversary. It's something else at these far reaches. The Cold is jarring on the system, particularly when you are in and out of the water. It has a presence to the point of almost being visible. Blizzards march vast distances across the tundra. The surface of the ocean suddenly freezes (as does my beard, if wet). The ice changes. And everything happens so quickly here that you need to be entirely focused. Exposed skin will crack, burn or freeze (or worse) in mere moments from wind, sun or cold. The most powerful forces that nature has lie dormant waiting for a moment of its choosing, and we are simply at the whim of it, hoping and preparing as best we can. Occasionally the weather is merciful, occasionally it does relent. And when it does, the spectacular beauty in the distance, usually obscured by snow and cloud, is unveiled.

On my first trip to Antarctica there was one particularly beautiful day. The glaring sun beat through a cloudless sky. The water had not even the slightest turbulence from wind – a gentle, rolling swell lapped the shores. Strangely, the water was even free of ice at the time. It almost seemed tropical, if you ignored the wildlife. The penguins performed their dances, as they followed us around as we hiked. They talked amongst each other and the young huddled closely. The fur seals battled and yelled. The odd elephant seal gurgled and roared. We wandered around, and did what we were there for, dwarfed by a nearby peak. The wildlife was truly awe-inspiring.

_Photo Jack Jeffress

Home base, for this journey, was a beautiful old tall ship captained by a woman raised by the polar regions. She was a truly rare and impressive person, and she had seen it all. She knew this area and its secrets better than anyone else I’ve met before or since. We soon heard her over the radio, with a pressure in her voice that was unusual. The message was clear and urgent, we needed to leave immediately. There was no time to waste.

We looked around – the sky was blue, the water was calm, and the wildlife was tolerating us well enough. It was hard to understand what invisible signals she had seen. But when someone that experienced speaks, you listen. And so we began to hurriedly move people back to the boat. The zodiacs were working double-time, shuffling gear and people back to the main ship (which was then, maybe, 500 metres away). The first trip went fine, the second one was okay, the third one was rough, and the fourth one… By the time the fourth trip came around, the one to pick us up, everything had changed.

Now in the water, we were fighting an onslaught of shifting ice to make way for the zodiac. There was a frozen wall around the shoreline that seemed to get higher and thicker every second. The seas were no longer calm. A short-period swell, with winds gusting 45 or 50 knots per hour, pushed endless ice in our direction. It was a drastic shift, and for a while we were convinced we would be stuck for at least the night. Eventually we did make it to the boat, though that didn’t mean the struggles were over. Trying to get the last of the gear up onto the main ship was a challenge. The zodiacs were battered and beaten against the hull, people were thrown around. And then we had to lift the zodiacs out of the water. They fluttered like falling leaves as they were hauled up and out of the water. In just 15 minutes, the calmest day we had seen so far turned into absolute chaos. The katabatic winds from the mountains were the culprit. Walls of frigid air careened down the slopes, seemingly intent on reminding us of our complete vulnerability in this alien environment. Lessons of weather are taught again and again in the polar regions. You learn to trust your instincts, trust the people around you, and pay attention to the things you never needed to notice before.

Everything in the polar regions is more difficult, and even simple tasks are things you need to prepare for. Surrounded by so much ice, I’d imagined getting water when camped on the tundra would be easy. It is anything but. The waters of the ocean typically begin to freeze at around -1.8 degrees Celsius (28.4 degrees Fahrenheit), and that sea ice is what you are standing on. It's salt water, not fresh water. Resources are limited so even though you could extract the salt, it's easiest to try to find any fresh water that is around. And because of that you are on constant lookout for icebergs or glaciers. So when you do see an iceberg in the tundra it’s a remarkable feeling. It means you have a job to do - you have to get there.

Crossing the tundra and its endless undulations, leads, sastrugi and ridge lines is hard work, and wildlife can hide all around. Some of that wildlife, the polar bear in particular, searches for you. You are nothing but an intruder and a resource to it. Even on snowmobiles, they will hunt and chase you for as long as they can, and they are smart and ultimately focused. They hide behind the ridges, they cover their noses (because they stand out) and often hide in the glare of the sun. They are beautiful, but they are also ferocious predators – extremely fast, highly capable, unstoppable and relentless. So, you have to be hyper-aware – you look everywhere and you listen keenly.

Once you arrive at the icebergs, it is time to get to the real work. You may still have to cross leads, acting as moats, around these frozen giants. The lower sections can still be made of saltwater as the waves crash and freeze on the foundations. You have to climb to get to places where the waves cannot reach – all the while being aware of the threats that may be lurking below. You cut big chunks of ice off, and that is what you will melt down and drink once back in camp. Simple tasks, things like getting water, can be risky here, and they demand your entire attention.

These complications and challenges make the beauty even more potent, they serve only to amplify (as always). The wildlife here is breathtaking. You quickly see that cold does not mean lifeless, and that in an environment this harsh and unforgiving, everything congregates. Millions of penguins cover entire landscapes, and their squawks echo in the valleys. The young huddle together, and the older ones hunt and find each other amongst the masses. They are inquisitive and converse as old friends do. The skuas hover overhead, prepared to predate whenever the opportunity arises. The fur seals bicker, battle and taunt each other and the males fiercely protect their harems. The elephant seals gurgle and impose their presence. All of this wildlife, in one way or another, is here due to one reason – the krill. This seemingly endless food source plays a role in almost any animal that resides in Antarctica's diet. The penguins enter the water to hunt the krill, the other seabirds dive and swoop. The leopard seals have their sights set on the penguins. Though these are not the only players in this game. The orcas and great whales are ever-present and soon assert their dominance, with displays of herding and bubble net feeding. Their cooperative hunting efforts show time and time again that these great predators are the result of millions of years of evolutionary perfection.

In the frozen kingdoms, life cycles are accelerated and you can witness them playing out absolutely everywhere. In the fjords of northern Norway, the herring gather in schools so thick that it seems like the whole seafloor is ebbing and flowing. The orcas, the absolute apex predators of any sea or ocean, come to the fjords for these fish. They work together in a way so streamlined and efficient, that it almost seems choreographed. Carousel feeding is how they predate here. The first step is echolocation. They can detect herring from distances that don't make sense. Once the orcas arrive, they divide the fish into bait balls of between two and seven metres wide. These bait balls are so dense you can see nothing else - just pulsating black clouds of life. Orcas are extremely vocal in these moments, their clicks and whistles fill the ocean. They know to bring the herring to the surface or to the shorelines, as they act as a natural barrier for the prey. And then they attack.

Jack wearing the Helly Hansen Arctic Patrol Modular Parka. Our most advanced parka to date made for the harshest cold conditions there are.

Time seems to speed up. As the main group of orcas continue herding the fish into tighter and tighter balls, others start to feed – and they take turns. They charge into the schools and then backflip, stunning the herring with their flukes. They usually eat fish one by one (surprising for an animal of this size). These social carnivores are unbelievable, although they do get taken advantage of. Sometimes, and this is something to be very wary of when in the water, the humpbacks, minke whales and fin whales find these masses of herring. They wait patiently for the orcas to do all of the hard work, drawing the herring into bait balls, and then they hurtle from the depths below, mouths like endless voids, swallowing absolutely everything in their path. Feeding events like this, in the shadows of towering peaks or under the shimmering curtains of the aurora, are remarkable and I will remember them forever.

These cycles repeat over and over again day in and day out, and they are true marvels to witness. When surrounded by wildlife gatherings of such magnitudes, you are so deeply immersed in nature that it’s easy to feel disconnected from humanity. It seems so distant, so surreal. But in reality, that is far from true. You are always connected – to your team, to the extraordinary gift you are sharing together, and to those who visited before you.

One of the most surprisingly profound things about time in the polar regions is the special kinship you feel with those who forged the paths you follow. They leave their lessons and resources behind. These lessons were hard-won and earned at huge cost, whether through defeat or victory. It is best to heed their warnings and follow their lead.

In Antarctica you see the stoic remains of refuges or structures left by people long ago. These remains are caught somewhere between standing strong against the endless onslaught of weather, and being completely overwhelmed.

In the Arctic you see the Inukshuk. Giant stone statues, human-like in form, almost glowing with power as they watch over the harsh and barren landscape. They mark good hunting regions or food caches, act as warnings for particularly dangerous areas, commemorate sacred places or loved ones, and serve as navigational points. In a region that seems so isolated, to see such clear evidence of people is powerful. This unwritten frozen code, to aid those who follow, is something you need to abide by too. It’s your responsibility to pass on what you have learned to make the path safer and easier for the ones who come next. This connects you in an unusual way, but it also signifies something that will soon come for you.

Eventually, you will leave here. Eventually, you will return to civilisation. You may face the infamous Drake Passage – the winds and waves intent on destroying everything in their path. You may face a tundra with ice starting to break up – its cracks expanding, trying to draw you into its frigid maw. But if you’re prepared, learned from your predecessors, and are lucky, you return. You are greeted by the smiles and hugs of friends and strangers alike, and your phone's notifications. You regale stories that speak of experiences that almost don't seem real, even to you, and that few can relate to. All the while the echoes of all of those moments reverberate in your mind – the whales are still singing, the orcas are still clicking, the penguins are squawking and the seals (if south) and bears (if north) are still growling and battling. These sights and sounds, and the memories associated with them, are imprinted on your soul. They shape you and, believe me, you will look back at them more than you’d ever think possible.

The polar regions have an unrivalled beauty – they are breathtaking in the realest sense of the word. Every time I have visited there, a part of me stays behind in the ice. These areas have the capacity to overwhelm and overpower you at any moment, and you must be willing to accept that. That acceptance forces a shift in perspective. Your approach to everything warps, and molds, and melts. In every sense you are dwarfed, and yet in a way these lands magnify. In the quiet you can't help but have sincere moments of introspection. There are infinite lessons to be learned from these landscapes, from the people you are with, and from the people who came before you. I plan on learning as much as possible.

In some ways, these ice paradises are where I am most at home. They have taught me more than any other place on Earth. Returning is by no means promised. But I will do everything in my power to be back, even more prepared than before, to see these frozen worlds – and I can't wait. Polarhullar will forever be my companion. If you ever get the opportunity to experience these magnificent environments – don’t hesitate, just go.